Most executives can’t differentiate between two very similar phrases – “digitalisation” and “digitisation”.

This matters because they are endeavours that have very different levels of risk and will likely produce very different levels of success or failure.

Digitalisation occurs when you take an existing offline, paper-based process and move it online. You might engage your design team, have arduous meetings about the colour of your data capture forms and the psychological significance of blue.

But whether it takes months or minutes, this process is a pretty finite one and essentially moves you from A to B, without anyone in your organisation being required to do anything radically different.

Digitalisation should happen as a part of “kaizen” (the Sino-Japanese word for “continuous improvement”) within an organisation and often takes place during a natural evolution of norms, such as going from using landline phones exclusively in an office, to purchasing company cell phones for near enough the entire workforce.

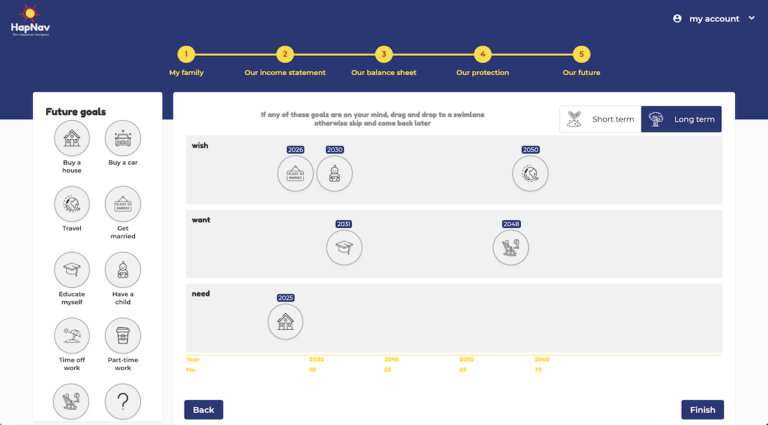

Digitisation is when you re-engineer the end-to-end process for a mobile-first world, often creating a new business model along the way. This is much more involved than dragging and dropping a form block and usually comes with a lot more debate.

True digitisation is often about building a digital process where there are no humans involved. An example is instantly transferring money to a friend for your half of the dinner bill, as you can with Revolut or Monzo. That process is much harder from an I.T. standpoint.

All this digital transformation in its various guises is great but how can companies determine the best digital direction to pivot towards, without the project being too taxing on business-as-usual ops or being too difficult to convince board members to back?

As with any use case or internal pitch, starting with the “tell” of digitalisation is overwhelmingly the formula that gets buy-in quickly, fuels momentum and releases human resources and budget.

The results in this category of project are quantifiable by nature, which is something most organisations are happy to commit to. You can speak about the number of sales that are likely to happen as a direct result of prospects downloading your PDF reports on commodities performance or the advent of AI, to name a few possible carrots.

The “tell” of digitisation, however, is usually the preserve of organisations with either enough brand confidence and financial reserves to pick themselves up after a potential flop. See Coca-Cola’s TAB drink and its subsequent scrapping of this unpopular and expensive project. This is an example of a behemoth unafraid to respond to the direction that the market is going – healthier beverages, in this case.

Proving digitisation requires the long view. As well as constantly surveying clients or customers to gather feedback, those brave innovators also look to the future, their competitors, their best minds, because they understand that clients and customers will most likely never tell you “That’s what I need” before giving you a billion dollar idea for the next iPhone.

Everything they will tell you is likely to fall under kaizen. No Rio or Sony MP3 user ever asked for an iPod. No Motorola Razr user ever asked for an iPhone. No Blockbuster DVD renter ever asked for Netflix.

So the simple takeaway again – digitalisation comes from listening to customers and striving for kaizen. At best, it adds a few pennies to the bottom line. Digitisation, on the other hand, is transformational when you get it right and does not derive from what already exists.

We can laugh at the Elon Musks of business and their ‘crazy’ endeavours all we want, but their brand of bravery is what put man on the moon.

Request a demo by contacting the Envizage team.