“Advice” is a popular word in the financial industry these days. It’s also a word that, in our opinion, has been misappropriated and stripped of its real meaning. We feel bad for it. So we are going to do our best to defend its honour.

The so-called “advice gap” is huge. Up to 10 million people in the UK are no longer able (or prepared) to pay the cost of traditional advice services, but urgently need to save if they are to have any prospect of a financially secure retirement. If that wasn’t bad enough, we have a global savings gap to match, with people in the USA and UK facing an intergenerational deficit in excess of $10,000 a year (over 20% of earnings).

In order to solve the pressing financial problems facing society, something needs to change. Advice needs to mean something once again.

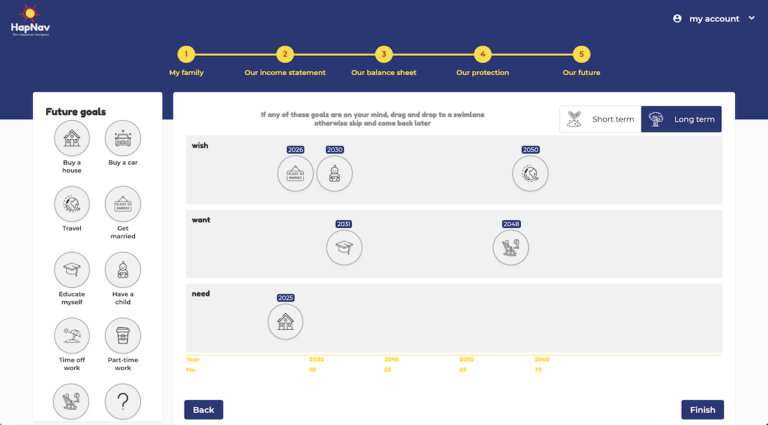

Before going into what constitutes good advice, it’s worth considering the kind of “advice” being offered by incumbents and disruptors today. It tends to involve questions that are impossible for most people to answer unless they are financial experts. It’s dominated by out-of-context “risk” questionnaires that ask questions most people don’t understand. And it revolves far too much around financial products, rather than the everyday lives, needs, and aspirations of individuals and their families.

Either the majority of financial service providers don’t know what constitutes good advice, or they are being forced – by regulation – to mislabel compliance journeys as “advice”.

Advice should not require consumers – or advisors for that matter – to respond to questions they cannot possibly answer. Questions like:

- What do you think inflation will be for the next 50 years?

- How long do you think you will live?

- How will you feel if the markets drop 20%?

True, some financial services firms are pitching tech-enabled “digital advice” alternatives to this old-school approach. But their “advised” propositions don’t actually offer advice. If you read the fine print, you may see that they offer something called “restricted advice”. Only they – and their regulator – understand what this means. When somebody is seeking advice on the right course of action for their future, these “advised” alternatives instead answer the question “which of our six portfolios is right for you?” These solutions are of limited use because they fail to help people answer meaningful questions about their futures. And that is one reason why they don’t scale.

In our view, this is compliance and should be presented as a series of steps required by the regulator before a bank can sell investment products to its customers. It is not advice. Frankly, no one should be surprised that there’s an advice gap in the UK when customer outcomes appear to be an afterthought, and digital journeys are still product-led instead of consumer-led.

Financial institutions want to sell their products in a compliant way, as they well should. But most of us don’t think about our lives in this way. We think in terms of aspirations, wants, needs, experiences, and responsibilities. The problems we are trying to solve aren’t necessarily concrete and quantified in numbers. They’re vague and hard to pin down, which makes them all the more challenging to solve.

Advice should not be confused with compliance. Both are necessary, but without proper advice, a compliance journey is meaningless for most of us.

In our next post, we will go into what we believe constitutes good advice.

The Simpsons” TM and (c) Fox and its related companies. All rights reserved.